“], “filter”: { “nextExceptions”: “img, blockquote, div”, “nextContainsExceptions”: “img, blockquote, a.btn, a.o-button”} }”>

Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members!

>”,”name”:”in-content-cta”,”type”:”link”}}”>Download the app.

There’s no shortage of yoga poses that are considered hip openers. These well-known postures that are commonly requested by students include shapes that focus on hip external rotation, or turning the thigh bone away from the midline of the body and stretching the muscles along the inner thigh. But that’s not the only way the hip can open. The opposite movement, known as hip internal rotation, turns your thigh bone toward the midline of the body and engages different muscles. And it’s largely missing in traditional yoga.

Anatomy of Hip Internal Rotation

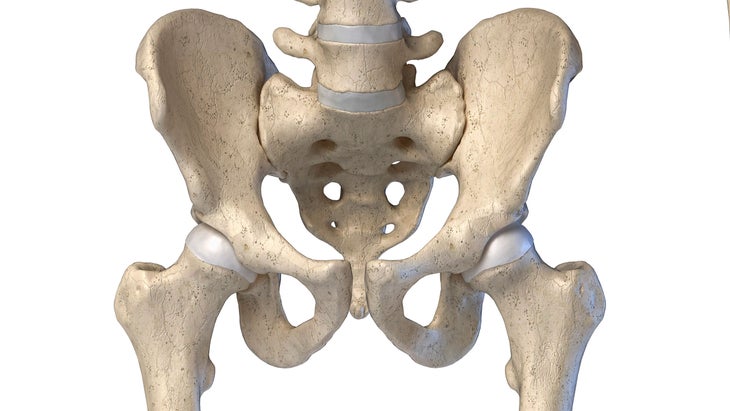

The thigh bone (femur) and hip joint are a ball-and-socket joint, which means the head of the bone sits like a knob in the hip socket. This enables the thigh bone to move in 360 degrees.

When contracted, the hip internal rotation muscles pull the thigh bones toward one another. These include the anterior fibers of the gluteus medius and gluteus minimus, the tensor fasciae latae, adductors, and the pectineus. Although internal rotation is essential to everyday life, many of us experience more limited range of motion here than in external rotation.

Part of this difficulty for yoga practitioners may be due to the fact that only a limited number of poses emphasize the internal rotators, among them Eagle (Garudasana), Hero (Virasana), and Lord of the Fishes (Ardha Matsyendrasana). You may have also experienced teachers encouraging internal rotation in certain poses. For example, in Tadasana (Mountain Pose), you might hear the cue to internally rotate your hips by “turning your inner thighs toward each other” or “reaching your inner thighs toward the wall behind you” to counteract the body’s tendency toward external rotation.

But you practice external rotation each time you come into Warrior 2 (Virabhadrasana II) or take your front leg into Pigeon Pose (Eka Pada Raja Kapotasana) or engage in most standing and seated poses. In a practice that is about finding balance—and not just the kind you experience while standing on one leg—it’s interesting that there isn’t more emphasis on hip internal rotation.

Why You Need Hip Internal Rotation

“This movement is often overlooked in most exercise modalities,” says Antonietta Vicario, yoga teacher and chief training officer at Pvolve, perhaps best known as Jennifer Aniston’s workout regime.

“Our hips need to move through their full range to stay mobile. Any dominance of specific movement patterns can create an imbalance in the body, which can lead to overuse and even injury over time,” says Vicario. “When the hips are tight, other compensatory muscle patterns will take over, which can lead to movement dysfunction.”

They internal hip rotation muscles also contribute to overall well-being before, during, and after menopause, explains Vicario. “During the menopause transition, our bodies start to lose muscle mass. We need to offset this through weight and resistance training,” she says. “Training lower body strength, mobility, and stability proactively protects our movement longevity.”

Practicing internal hip rotation also allows for better blood flow to the back of the joint capsule, explains yoga teacher Nicole Sciacca, which encourages “reduced inflammation, articular resiliency, and lubrication for the joint itself.” A Functional Range Conditioning mobility specialist, and Kinstretch teacher, Sciacca ensures her training includes internal rotation because it helps her hip joints feel better. “After 30-plus years of dance and nearly 20 years of yoga practice, I like to think I’m doing my due diligence in training my internal rotation now,” she says.

Strong hip internal rotators support a well-functioning pelvic floor. Lauren Ohayon is a pelvic floor specialist, yoga teacher, and founder of Restore Your Core has studied functional range conditioning (FRC), which trains the body in movements that mimic everyday activities. Ohayon has observed many dysfunctional issues in students who lack internal rotation mobility, including lower back pain and a hypertonic (overly tense) pelvic floor, although she is careful to point out that the relationship is not necessarily causal.

Adding internal hip rotation to your yoga repertoire may offer even more unexpected benefits. “The greatest predictors of longevity are the strength and flexibility of our legs,” explains Reuben Chen, MD, board-certified sports medicine physician, holistic pain management expert, and chief medical advisor at Sunrider International.

“It is important to provide some balance to the muscles around the joints, as well as balance to the entire joint,” says Chen. “If there is imbalance in the musculature due to movements that cause extreme motions on the joints, such as with gymnastics or extreme yoga positions, this will cause uneven wear in the joints which can lead to a breakdown of the cartilage.”

Think back to all the time you’ve spent cringing while holding your knees apart in Goddess Pose (Utkata Konasana) and Bound Angle Pose (Baddha Konasana). You may want to start catching up by practicing poses that target the opposite movement.

How Do You Practice Hip Internal Rotation?

Internal rotation stretches aren’t the most comfortable for everyone. “The lack of ‘cushion’ between the head of the femur and the joint capsule itself are what make it such a bizarre feeling for most and that does not typically go away over time,” says Chen. However, he warns students to discern between discomfort and impingement, which is when the head of the femur bone is displaced or jammed into the hip socket.

For example, sometimes in Garudasana (Eagle Pose), there can be a sharp pressure at the top of the inner thigh bone. Some experience a similar sensation in Virasana (Hero Pose), which also requires internal rotation. Or you may not. It’s entirely personal based on your unique skeletal structure.

How to Include Hip Internal Rotation in Yoga

Ancient yoga texts, such as the Hatha Yoga Pradipika and Gheranda Samhita, feature an abundance of externally-rotated seated poses. One potential reason why yoga shows a bias toward this type of hip movement is the physical poses were designed to help us sit in meditation. The cross-legged meditation position requires external rotation in the hips.

Contemporary teachers may feel reluctant to adapt or change the “classic” poses in an effort to honor the tradition of yoga. But many well-respected teachers consider bringing a more balanced approach to be aligned with the intention of yoga. “It never seemed right that yoga was very external biased without a balance of internal,” says Ohayon.

Understanding that each pose was made up by someone who saw purpose in its shape can help provide context for the practice at large. Longtime yoga teacher James Morrison explains, “Every yoga pose ever invented is a variation on another yoga pose and/or product of the imagination of the practitioner.”

6 Hip Internal Rotation Exercises for Your Yoga Practice

Although the following exercises for hip internal rotation aren’t found in classic yoga texts, you can easily incorporate them into your practice. If you’re already familiar with some of these movements, consider increasing the frequency with which you practice them.

1. Windshield Wipers

You may have encountered this pose as a quick stretch at the beginning of yoga class or as a transition in between twists. But when you slow it down, it makes an excellent hip internal rotation stretch. Make sure your feet are wider than hip-width before letting your legs fall to one side. That distance creates space for the internal rotation in the hip of the top thigh.

How to: Lie down on your back, bend your knees, and bring your feet as wide as your mat. Let your knees fall over to your right side as you roll onto the edges of your feet. Your legs will be staggered. Remain here for 10 breaths. Come back to center and then switch sides. You can also practice this while seated with your hands behind you for support.

To intensify the stretch, explore resting the ankle of your bottom leg on your top thigh and allowing the added weight to help you deepen the twist, although remember to discern between discomfort and pain. If you experience any pain in your knees, immediately release the stretch.

2. Deer Pose

A common yin yoga pose that’s been making its way into some vinyasa classes, Deer brings the hip of the back leg into internal rotation. The stretch is popular among FRC communities, where it’s known as 90-90 given the shape it makes in your legs.

How to: From sitting, bring your right leg in front of you so your shin is almost parallel to the short side of the mat. Bring your left knee out to the side so your thigh is parallel to your front shin and your shin is perpendicular to your thigh. Your legs will be in an “S” shape consisting of two 90-degree angles.

Sit upright and press your fingertips onto the mat or blocks. Stay here or slowly lean your chest forward. Stay here for 10 breaths. If you’re folded forward, slowly walk your hands back and sit upright. Lean onto your right hip and swing your left leg forward. Pause with your legs straight in front of you and then switch sides.

3. Lunge Variation

Ohayon likes to incorporate internal rotation when she teaches a lunge. As with Windshield Wipers, this variation works only when your feet are wide enough apart to allow space for your back leg to internally rotate.

How to: Come into a lunge with your right foot forward and your hands on blocks on either side of your front foot. Shift your back foot to the left about six inches. Begin to internally rotate your back leg so your toes begin to turn inward. As you circle, keep the movement isolated to your thigh bone so your pelvis remains stable and your hip bones continue to face the mat. Your front leg and foot will probably want to roll outward in external rotation, so press into your front heel to counteract that. Imagine your thighs are rolling inward toward each other. Stay here for several breaths.

Return to your lunge and then step through Plank or Downward Facing Dog before switching sides.

4. Warrior 3 (Virabhadrasana III) Variation

Ohayon teaches her students to come into this Warrior 3 variation from the Lunge Variation discussed above, which further strengthens the hip internal rotators of your back leg.

How to: Come into the Lunge Variation above and walk your blocks a few inches in front of your shoulders. Maintain the internal rotation action of your back leg as you slowly lift it and straighten your standing leg, coming into Warrior 3. Your focus is more on internal rotation than balance, so consider keeping your hands on blocks. Stay here for several breaths. Slowly lower your lifted foot alongside your standing foot and come to standing before exploring your other side.

5. X Legs

This exercise challenges not only your hip internal rotation muscles but your balance. Using blocks beneath your hands can help you navigate the field trip to the other side of your mat with more steadiness.

How to: Come into the Lunge Variation above with your right foot forward and your hands on blocks. Begin to walk your hands and blocks to the outside of your right leg and place your blocks beneath your shoulders. Roll onto the outer pinky-toe edge of your left foot. Now roll onto the outer edge of your front right foot. You might need to maintain a bend in your front knee. Start to straighten both legs as you draw your thighs toward each other. Breathe here.

Slowly walk your hands back toward your front foot and come back to a Lunge. If you like, practice Plank or Downward Dog before practicing it on your left side.

6. Three-Legged Dog Circles

You may already practice these slow and subtle circular movements without knowing they’re a form of controlled articular rotation (CARS), a type of movement that can support long-term joint health and mobility. Sciacca and other teachers commonly incorporate CARS into classic poses, such as Downward Facing Dog.

How to: Come into Downward-Facing Dog. Lift your right leg behind you and bend your knee 90 degrees so the bottom of your foot faces the ceiling. Start to make extremely small and slow circles with your thigh bone. Keep your pelvis stable so your hip bones continue to face the mat as you circle, taking your thigh just a few degrees to the right, then inward toward center (this is internal rotation), and then back to starting. Make 5 circles. Come back to Down Dog and switch legs. You can also practice this from hands and knees or standing at a wall.

RELATED: 9 Ways to Modify Yoga Poses to Emphasize Internal Hip Rotation