Methods

Stimuli, design, and procedure

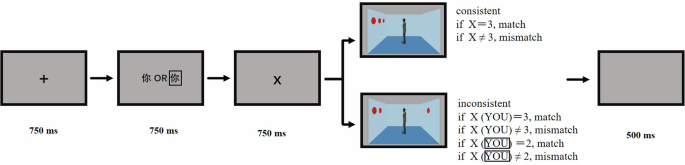

In this experiment, we used the same stimuli and procedures as in Experiment 2a, except for the avatar identity. The experimental instructions informed the participants that the avatar in the room represented themselves. To indicate the perspective, the word “你” (Eng.: YOU) or “你” appeared for 750 ms, indicating which perspective had to be judged. “你” represented the participant’s self-avatar in the room (Fig. 7). The study used a 2 (group: patients with SZ and healthy controls) × 2 (consistency: consistent and inconsistent) × 2 (perspective: one’s own and self-avatar) factorial design.

Statistical analysis

We excluded the data from the practice trials. The response latency results were preprocessed, and trials with errors were removed. Only the response latencies falling within ± 3 standard deviations of each participant’s average response latency were considered. In total, 20 patients (15 with accuracy rates not exceeding 80% and 5 with an average response latency exceeding 3000 ms) were excluded from the analysis. All data were analyzed using IBM® SPSS® Statistics Version 23.0 via a 2 (group: patients with SZ and healthy controls) × 2 (consistency: consistent and inconsistent) × 2 (perspectives: one’s own and self-avatar) repeated measures ANOVA.

Results

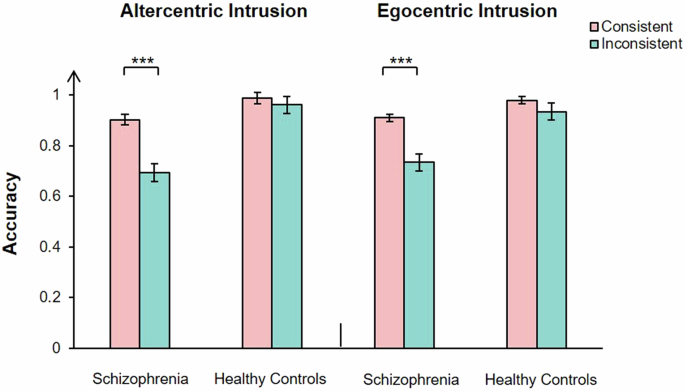

Accuracy rate

A significant main effect of group, F (1, 66) = 42.20, P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.39, and consistency was observed, F (1, 66) = 46.84, P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.42. There was no significant main effect of group perspectives was observed, F (1, 66) = 0.03, P = 0.87. There was a significant interaction between group and consistency, F (1, 66) = 22.45, P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.25. There was no significant interaction between group and perspectives, F (1, 66) = 1.05, P = 0.31, consistency and perspectives, F (1, 66) = 0.03, P = 0.86. There was no significant interaction between group, consistency and perspectives, F (1, 66) = 0.59, P = 0.45. The simple effect analysis showed that, patients showed higher accuracy rate in consistent perspectives condition (M = 0.91, 95% CI [0.88, 0.95]) than inconsistent perspectives condition (M = 0.71, 95% CI [0.67, 0.76], t (65) = 5.74, P < 0.001, Cohen’s dz = 0.71. Healthy controls show no significant difference in accuracy rates between consistent perspectives (M = 0.98, 95% CI [0.95, 1.02]) and inconsistent perspectives (M = 0.95, 95% CI [0.90, 1.00], t (69) = 2.28, P = 0.14)(Fig. 8).

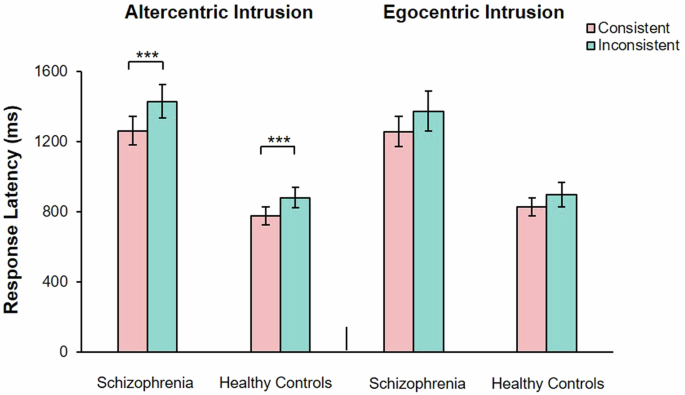

Response latency

A significant main effect of group, F (1, 46) = 21.00, P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.31, and consistency was observed, F (1, 46) = 26.57, P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.37. There was no significant main effect of perspectives was observed, F (1, 46) = 0.003, P = 0.96. There was no significant interaction between group and consistency, F (1, 46) = 1.60, P = 0.21, group and perspectives, F (1, 46) = 1.74, P = 0.19, consistency and perspectives, F (1, 46) = 1.89, P = 0.18. There was no significant interaction between group, consistency and perspectives, F (1, 46) = 0.06, P = 0.82. The simple effect analysis showed that, all participants showed longer response latency in inconsistent perspectives condition (M = 1144.85, 95% CI [1025.19, 1264.51]) than consistent perspectives condition (M = 1031.02, 95% CI [933.92, 1128.12], t (108) = 4.56, P < 0.001, Cohen’s dz = 0.64) (Fig. 9).

Discussion

Experiment 2b revealed that patients with SZ showed altercentric intrusion and had a higher accuracy rate and shorter response latency in consistent perspectives than in inconsistent perspectives of one’s own condition. In the self-avatar condition, patients with SZ showed egocentric intrusion and had a higher accuracy rate for consistent perspectives than for inconsistent ones. These findings suggest that avatar identity can influence the implicit visual perspective-taking abilities of patients with SZ. Specifically, increasing the salience of the avatar’s identity can enhance patients’ awareness of perspectives, thereby prompting them to actively adopt the other’s perspective. In addition, patients with SZ showed altercentric intrusion in accuracy rate and response latency in this experiment. This may indicate that patients have the ability to spontaneously adopt the avatar’s perspective.

General discussion

The current study explored whether patients with SZ can spontaneously adopt others’ perspectives and the influence of avatars on this spontaneous process through an implicit visual perspective-taking task. We found that patients with SZ were capable of spontaneously adopting perspectives; however, their ability to do so for strangers was impaired, with their spontaneity being influenced by the identity of the individual whose perspective was being considered.

Visual perspective-taking is a fundamental component of ToM24, which humans gradually develop as they grow and mature. The findings of Experiment 1a indicating that patients with SZ were unable to spontaneously adopt the perspective of other avatars, it consistent with those of Kronbichler et al.4. In this experiment, participants were presented with only one avatar in the stimulus images and informed that the avatar was a stranger. In addition, the experimental instructions did not provide any details about perspective-taking. Healthy controls succeeded in spontaneously perceiving others’ perspectives, pointing toward an impairment in the spontaneous adoption of others’ perspectives in patients with SZ.

The following question remains: Is patients’ inability to spontaneously adopt others’ perspectives due to a disregard for other people or a lack of awareness of the existence of others’ perspectives? For patients with SZ, their illness affects most aspects of their cognitive abilities, such as their inability to focus well on objects in environment21. Consequently, they may fail to recognize the presence of additional information while performing experimental tasks, especially when such information seems unrelated to the current task. This may not reflect their inability to spontaneously adopt others’ perspectives but that they overlook doing so. According to O’Grady et al.20 in uncued tasks where the potential relevance of perspective-taking is unrecognized, spontaneous perspective-taking does not occur; however, when attention is drawn to the avatar, it does. Therefore, we conducted Experiment 1b.

To increase participants’ awareness of the avatar’s perspective in Experiment 1b, we changed the identity of the avatar from a stranger to the participants themselves. The existence of impairments in recognizing others’ perspectives has been verified in patients with SZ. Recent research has revealed that during the process of reflecting on others, patients with SZ exhibited reduced activation in the right temporoparietal junction—a brain region associated with self/other differentiation and social cognition. This indicated a failure in processing self- and other related information, which may lead to altered judgments of others’ behaviors25. This reduced activation could be a contributing factor to the impaired ability of patients with SZ to adopt others’ perspectives. However, Experiment 1b revealed that even when the avatar represented themselves, patients were unable to perceive the avatar’s perspective without cues, unlike healthy controls. These results indicated that patients with SZ were unable to adopt others’ perspectives spontaneously without being prompted. This may be due to impaired spontaneous perspective-taking or impairment in recognizing others. Another possibility is that the current task did not explicitly make the patients aware of the existence of perspectives. When patients perceive perspectives as irrelevant to the task at hand, they may not actively consider those of others20. Therefore, we decided to use the cued task to explore the participants’ ability to spontaneously adopt others’ perspectives.

Experiment 2a found that patients with SZ exhibited altercentric intrusion in response latency but not in accuracy rate. However, healthy controls showed altercentric intrusions in both indices. This may underscore patients’ difficulty in perceiving others’ perspectives spontaneously, which is consistent with the findings of Drayton et al.19 and Kronbichler et al.4. The response latency results indicated that patients with SZ may be influenced by others’ perspectives, albeit not as strongly as healthy controls. Simultaneously, it may also indicate that patients possess the ability to spontaneously adopt others’ perspectives. We conducted a final experiment to ascertain whether patients’ spontaneous adoption of others’ perspectives is influenced by avatar identity or spontaneous ability. The results revealed altercentric intrusion in the patients, as they spontaneously perceived a self-avatar perspective when the task required them to adopt their own perspective. Therefore, patients with SZ were capable of spontaneous perspective-taking.

Based on the combined results of all experiments, spontaneous perspective-taking was influenced by two factors in patients with SZ. The first factor was the awareness of perspectives. Previous studies have explicitly suggested that even in healthy individuals, the adoption of others’ perspectives may not always occur without explicit cues26,27. In daily life, to acquire valuable resources, individuals tend to spontaneously attend to information relevant to themselves. However, patients with SZ have been proven to exhibit attentional impairments, such as difficulties with sustained attention and controlling selection28,29. Recent research has indicated that patients with SZ exhibit stronger and spatially broader visual information filtering around their attentional focus compared with healthy individuals. This increased filtering of visual information beyond the focus of attention may affect higher-level behavioral, emotional, and cognitive domains30. Therefore, attentional impairment may hinder the spontaneous adoption of alternative perspectives unless their existence is explicitly emphasized for the patients.

The second most influential factor was the identity of the avatar. Previous studies have confirmed that nonsocial cues, such as triangles, fail to elicit spontaneous perspective-taking processes in patients with SZ18. The present study indicated that human avatars possessing social cues can also affect the spontaneity of patients’ perspective-taking processes, contingent upon the avatar’s identity. Keromnes et al.31 found that during visual recognition tasks, patients tended to focus on their own images, which led to significantly early self-recognition but delayed recognition of others. In visual perspective-taking tasks, patients’ difficulty in recognizing others affected their spontaneous perception of others’ perspectives. Compared with other avatars, embodying themselves was more likely to elicit their attention from the avatar’s perspective.

Our study had some limitations. First, in both the explicit and implicit visual perspective-taking tasks, the premise behind patients with SZ adopting others’ perspectives is that they understand that avatars in different locations may be able to see content that they cannot. We found that patients exhibited altercentric intrusion for the self-avatar identity, possibly indicating that they could comprehend that the view differed in different positions. However, this could also stem from patients’ abnormal self-perceptions32, as their arbitrary switching between the self and self-avatar may have influenced the experimental results. Therefore, future research must clarify patients’ ability to comprehend the differences between others’ and their own perspectives from diverse locations by incorporating cognitive neuroscience techniques to enhance the reliability of the findings. Second, a unique connection exists between individuals at high risk for SZ and patients with SZ, along with the abnormalities manifested in ToM33. Future research should delve into the performance of high-risk individuals in this task, particularly the uncued perspective-taking task, which may potentially serve as a method for the early identification of schizophrenic tendencies.

In summary, we found that patients with SZ exhibit a certain degree of altercentric tendency in implicit visual perspective-taking tasks, displaying altercentric intrusion when patients become aware of their own perspective existing in another spatial location within the scene. We suggest that patients with SZ are capable of spontaneously adopting perspectives, but this process is influenced by the degree of attention paid to the perspective and identity of others. This study provides insights into the social cognitive processes of patients with SZ. Future research should comprehensively look into the role of other individuals’ identities in the process of social cognition.